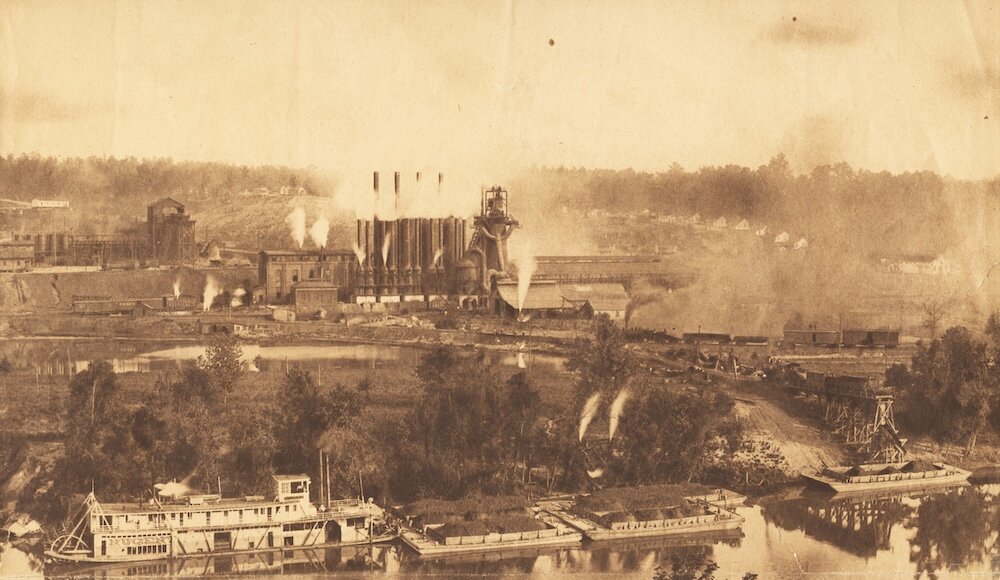

The photograph first appeared in an October 1915 special industrial section of the Birmingham Post-Herald. The busy black-and-white image ran under the headline “LOADING COAL BARGES IN TUSCALOOSA COUNTY FOR EXPORT.” Coal-laden barges tethered to a steamboat rest on the Black Warrior River.

The vessels cast their reflection onto the stilled water, contrasting with the frenetic scene atop the bluff, where the smokestacks of the Central Iron & Coal Co. appear in full operation. They cast a haze over the scene that obscures momentarily many smaller structures in the background, including worker houses, tipples and buildings of subsidiary suppliers. Between the plant and the river is a railroad line where several train cars lie in wait.

Over the course of a day, the coal on the steamboat — which likely came from a mine less than 60 miles away — would be unloaded and replaced with finished cast-iron pipes. Back down the Black Warrior it would go, destined for dockside suppliers in Mobile or New Orleans who placed the pipes onto larger vessels and sent them out into a waiting world before repeating the journey. At the same time, men loaded down the railroad cars with pipes bound for inland suppliers. With a whistle and a groan, the heavy load moved along the tracks, the engine adding its own smoke and noise to the foundry’s din.

Tuscaloosans had long sought such an enterprise. The area provided ample resources, producing more than 200,000 tons of coal by the turn of the twentieth century. But with Birmingham in close proximity, attracting industry proved elusive. In the 1880s, after a potential development failed, county boosters devoted time and treasure to making the area a more attractive prospect. They secured several locks to make the mighty Black Warrior more navigable. They enticed new railroad investments and spur lines.

These efforts helped to bring to town the entrepreneurial Frank Holt. At first, this out-of-towner’s motives for seeking out a large tract of land were kept quiet. In 1901, he purchased some 1,200 acres of cotton fields and forest land a few miles upriver for an untold purpose. Plans were made known the following year with the incorporation of the Central Iron & Coal Co. The new plant along the Black Warrior River was a subsidiary of the New York-based Central Foundry Co., with locations in New Jersey, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania and Tennessee, along with Alabama-based foundries in Anniston and Bessemer.

The idea for this new industrial enterprise was simple: to provide cast-iron pipes for the many municipalities around the country putting in their first underground lines for water and sewer service. With frontage along the Black Warrior River and access to the railroad, the location Frank Holt chose was perfect for such a venture — and he was rewarded by having his surname grace the map, as it still does today.

With the foundry’s construction underway, the company’s investors looked farther afield to secure land that contained the essential minerals needed to produce iron and steel. Between Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, such places were still readily available. The closest location, named Kellerman Coal Mine after an early company engineer, was later connected to the foundry site by a railroad spur.

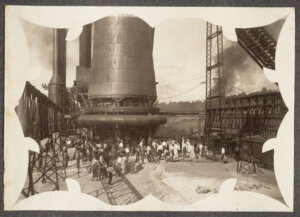

They lit the furnaces for the first time on Aug. 3, 1903. That honor fell to young Edith Lodge, daughter of the company’s first president, Joseph Lodge. At the time it went into production, the company could pour 150 tons of iron a day. Within a decade, that number doubled.

In 1910, the Central Foundry Co. in New York fell on hard times and went into receivership. Officials at the foundry in Holt were quick to allay local fears about the future of their thriving enterprise, which was then in the midst of an expansion. A few months later, receiver Waddill Catchings came to Alabama for an inspection tour. Apparently pleased with what he saw, Catchings continued to invest in the facility at Holt. When the conglomerate reorganized the following year, Catchings became its new head.

Expansion, not foreclosure, was afoot at the Central Foundry in Holt. In May 1911, 40 new ovens were constructed. Later that year, rumors circulated around Tuscaloosa County of an even larger investment there. In early December, Catchings himself announced the $800,000 expansion plan (akin to a $28 million investment today). “The news fired with new hope and enthusiasm the businessmen present who have been working for Tuscaloosa’s development,” wrote one reporter. So frequent were Catchings’ visits over the next year that many predicted he would relocate his corporate headquarters to the Yellowhammer State.

The elements of an expanded company town were soon evident at Holt: a commissary, school, homes for workers, doctor’s office, recreational offerings and a hotel for visiting businessmen. Still more workers came. One observer reported “Holt is about the busiest place on the map just now.” At night, locals from miles away would watch the flames from the molten pig iron runs reaching into the sky. Up close, the foundry sounded “like walking up to a hurricane,” a workman recalled.

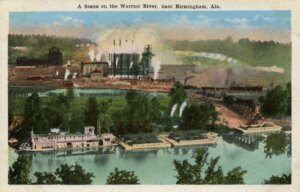

The name of the photographer who snapped the 1915 image is lost to history. But what he or she left behind was a glimpse of a company in full production, fulfilling both the expectations of its corporate investors and the dreams of boosters who built upon its success. If any locals purchased the colorized postcard of the image that was widely available by 1919, they likely scoffed at the description of the foundry as being “near Birmingham.” No — the Central, at least this Central, belonged to Tuscaloosa County.

There were good years and bad in the decades after the photograph. The Great Depression brought with it a yearslong shutdown. Critical war-related contracts in the 1940s helped save the business. Buoyed by a government-assisted wartime expansion and prosperous decades thereafter, the fires of the foundry burned until the early 1980s. An industry shift to plastic pipes brought the business that had long operated overlooking the Black Warrior River to an end.

Historian Scotty E. Kirkland is a freelance contributor to Business Alabama. He lives in Wetumpka.

This article appears in the September 2025 issue of Business Alabama.