Fewer innovations did more to connect Alabamians to the broader world than the radio. By the 1920s, new perspectives and access to music, sports and educational programming were suddenly available. Within two decades of the medium’s commercial availability, radio stations and their ubiquitous towers began to dot the Yellowhammer landscape. And yet during radio’s golden age, there was just one manufacturer of the devices in the entire state.

The man who made beautiful, early radios in Alabama was a Tennessean. Ernest W. House was born in Nashville in 1882. By 1900, he was living in Birmingham alongside his mother and grandmother. In 1921, he ran a typewriter repair business in a small shop in the Farley Building. At one point, he also worked as a stenographer for a local judge.

Although he lacked formal training as an engineer, radio technology captivated House, and he was an early experimenter with the devices. His daughter Lenora recalled: “He got so enthused over the fact that you could pick up a signal over the air on a little thing like that, that he just started learning about it on his own.”

By 1923, Ernest and his wife, Alice, were hosting “radio parties,” piping in programs from stations in surrounding states, some of which originated from faraway places like New York and Cuba.

House and other early radio owners found fewer Alabama-based options. Alabama Power Co. launched the state’s first radio station, WSY, in 1922. Conceived as a means of communicating to far-flung employees, the station also broadcast news and entertainment programs in the evenings. When the station ceased operations in 1925, the company donated its equipment to Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University). The college used the equipment to help launch WAPI, relocating the station to Birmingham in 1928.

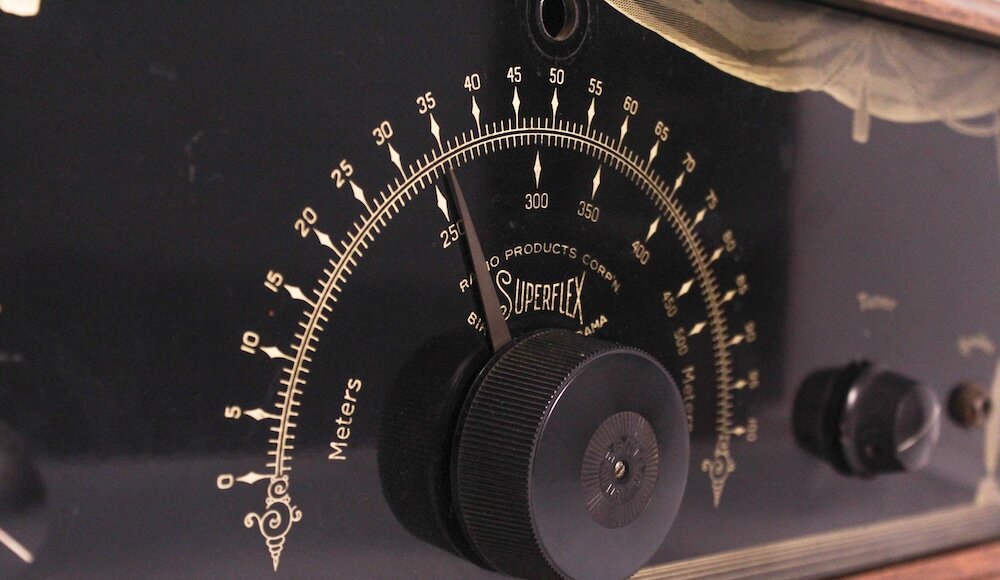

Early radios were difficult to tune. Most had a series of three or more dials that had to be carefully adjusted to locate stations. As he tinkered, House conceived a different solution to this conundrum: a basic regenerative electric circuit to manipulate the tuner. It took time.

“I remember the night Papa knew he had perfected the circuit,” his daughter remembered in 1990. “It was 3 o’clock in the morning.”

From that success in the small hours of the morning came Ernest House’s greatest contribution to the science of radio receivers. In 1925, he founded the Radio Products Corp. alongside Birmingham businessmen W. T. Estes and Jelk Cabiness. In August of that same year, he applied for a successful patent on his “radio receiving circuits.”

House named his new radio the “Superflex” and trumpeted its ease of use and clarity. “The ability of this wonderful circuit to let you listen to just ONE STATION at a time, even if another is as close as one half-mark away on the dial, will win your instant admiration,” read a company brochure. “Hear One – You’ll Buy It.”

With its hand-rubbed walnut finish and intricate gold detailing, the Superflex was a presentation piece. The company offered receivers in both tabletop and console models. Such artistry and innovation came at a price, however. Simpler models cost between $80 and $100. The larger console model that topped out at just over $210 would cost nearly $4,000 today.

“Buy Performance,” one ad reasoned. “This will stay with you long after price…[has] long been forgotten.”

In the fall of 1927, the Radio Products Corp. participated in a city-wide event to air a ringside broadcast of a boxing match between Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney. WBRC, a Birmingham-based station founded in 1925, aired the match. Atop their building, the makers of Superflex mounted three 11-foot-tall loudspeakers. As many as 4,000 people listened to the broadcast from the Radio Products Corp. Across the WBRC listening area, some 250,000 listened to the instant-classic known as the “Long Count Fight.” In the seventh round, Dempsey knocked Tunney to the mat but failed to quickly retreat to a neutral corner so the count could begin. Tunney rallied and won the fight — Dempsey’s last — by unanimous decision.

Two years later, the resourceful House tried to convince Alabama to put Superflex radios on a state contract. A few lines in Gov. Bibb Graves’ 1929 New Year’s message prompted the effort. Graves rightly discerned radio’s educational potential and was an early advocate for its expansion. “Radio has transformed the ether of the heavens into an agency of service to mankind,” he wrote, and called for the inclusion of radios in Alabama’s public buildings, especially its schools.

“We believe we might be in position to undertake this proposition as a factory, for our State,” House wrote to the governor. He further suggested that the Radio Products Corp., as the state’s only manufacturer, could also assist with installation and upkeep.

House’s proposition went unanswered. The governor’s lofty idea for radios in every classroom ran headlong into the cold, cash-strapped truth of the state’s financial situation. With the onset of the Great Depression just a few months later, even fewer radio enthusiasts could likely afford luxury items like the Superflex.

Work slowed at the plucky little factory along 28th Street North. As funds became scarce, its advertisements vanished from local newspapers and trade magazines. The Radio Products Corp. quietly faded away without fanfare. Ernest W. House remained in Birmingham for the rest of his life, working as a building contractor and tinkering with radios.

The precise number of Superflex radios produced is not recorded. The only two models known to still exist are both in the capable hands of the Alabama Historical Radio Society in Birmingham. Some of the society’s finest pieces are displayed in a small museum on the first-floor atrium of Alabama Power’s Birmingham headquarters, a fitting location given the company’s historic connection to radio in the state. It is even more appropriate that a pristine model of the Superflex, perhaps the finest that remains, is today cared for by people just as enthusiastic about radio as Ernest House was a century ago.

Historian Scotty E. Kirkland is a freelance contributor to Business Alabama. He lives in Wetumpka.

This article appears in the July 2025 issue of Business Alabama.