Hunter C. Haynes, one of the most successful barbering entrepreneurs of the early modern era, was born in Selma in 1867. The city and state were still adjusting to the effects of war and the early years of the Reconstruction era. His formerly enslaved parents moved to the city after emancipation.

At the age of 10, young Haynes began helping support his large family by working outside a local hotel — as a bootblack, cleaning and treating shoes and other leather goods among other tasks. This early exposure to handling leather served him well later in life.

After his father died, Haynes entered into an apprenticeship to become a barber. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, barbering ranked among the few professions that offered African Americans a certain degree of occupational status and safety. Because they catered to clientele of both races, skilled African American barbers often existed more freely in a segregated world. Thus, barbering was sometimes a means to entrepreneurship of other kinds, as was the case with Haynes. His work honing his tonsorial talents took him far beyond Alabama, to towering cities like Chicago and San Francisco. Still, his roots were in Selma. He returned home often.

Details of the young barber’s early career are few. Haynes appears in the 1888 Birmingham city directory, working under the tutelage of longtime barber George W. Jones. During the time Haynes was in his employ, Jones relocated his shop from 3rd Avenue to North 20th Street, a move which placed him at the very heart of the city’s central business district. An advertisement in The Birmingham News noted that Jones “employs popular and best barbers,” which can be taken as an indication of the talent of 21-year-old Haynes.

Haynes returned home to Selma around 1890 to ply his trade. While there, the barber won the affections of local schoolteacher Alice Reid. The couple were married in Selma in 1894. Alice played a key role in her husband’s professional career in years to come.

Masters of a craft often view their tools as extensions of themselves. And when those tools fall short, frustration sometimes leads to innovation — new and better paintbrushes and carpentry tools, for example. So it was with Haynes, who envisioned a major change among the most utilitarian of barbering implements: the razor strop.

The strop was a simple piece of leather, typically repurposed from old carriage harnesses. Most strops had a ring on one end and a handle on the other, allowing the user to quickly move the razor up and down the length of the strop. This action brandished and straightened the thin razor blades, which otherwise could warp and become dull, resulting in a miserable shaving experience. Prepping a new strop for use typically involved a chemical treatment or the use of jeweler’s rouge. It was a messy and time-consuming affair.

Drawing upon his experiences as a bootblack and his barbering knowledge, Haynes created a pretreated, ready-to-use strop. To perfect and market his invention, he made his way to Chicago, purchasing from pawnshops and other stores there as many old straight razors as he could find. He refined the blades then took them to area barbers as a way to demonstrate his new strop’s effectiveness, oftentimes selling both the strop and razors together. His cornering of the secondhand blade market earned him the sobriquet “King of Razor Traders.”

In his advertisements Haynes was circumspect about the “secret chemical mixture” he concocted to treat his strops. He did, however, note that each unit was subjected to his own rigid personal inspection. The Selma-born barber had himself become a brand.

For a number of years, he maintained residences in both Selma and Chicago. In these peripatetic times, Haynes worked to build his company. He traveled throughout Canada and Europe and demonstrated the “Haynes Razor Strop” at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. As the orders came in, Haynes rented a two-story building in Chicago’s 4th Ward. He employed a small number of workers on the first floor. He and Alice, who served as the company’s secretary-treasurer, lived upstairs. Haynes kept a separate office to handle his burgeoning mail-order business.

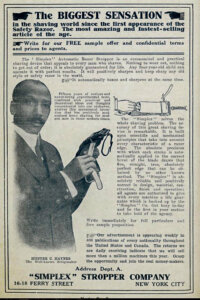

As Haynes and his small army of independent sales agents traveled throughout the country and abroad, they carried only a few items for immediate sale, funneling orders instead through the mail. Haynes also maintained sales connections with some of the leading African American newspapers of the era. For one 1902 promotion, he offered the readers of a Washington, D.C., paper a razor strop, straight razor and shaving brush for $3.00 (nearly $100 today). The advertisement showed an image of Haynes in a three-piece suit and sporting a well-kept mustache. He was the picture of success. A version of the ad eventually ran in some 400 newspapers.

In 1906, Haynes relocated to New York City, eventually establishing a business at 355 Broadway. The company produced 1,000 items a day from an expanded portfolio that by then included razors, barbering shears and different types of strops. In 1908, he sold 20,000 razors in New York City alone and entered into a successful partnership with German blade manufacturer Gottlieb & Hammesfaber.

The final act of his career was a bit of a pivot. He sold his interest in the razor strop company and established a film studio. Based in his Chicago home, Haynes created short film segments showcasing African American entrepreneurs and businesses. He also dabbled in a brokerage firm.

Haynes contracted tuberculosis in 1917 and spent the final year of his life in a “cure cottage” at Saranac Lake, New York, site of the nation’s first laboratory and sanitorium built for the study and treatment of the disease. Alice Haynes was by his side when he died on New Year’s Day, 1918. She dutifully fulfilled his final wish and buried him in the Haynes family plot in Selma, the city of his birth and where his roots remained through his many faraway adventures.

Historian Scotty E. Kirkland is a freelance contributor to Business Alabama. He lives in Wetumpka.

This article appears in the February 2023 issue of Business Alabama.