There are few immutable facts that ring throughout history. The human story is, at its very core, one of change. Sometimes that change is gradual; sometimes it arrives with alarming rapidity. Still, among those unalterable truths of existence, truths unbothered by events great or small, is the plain fact that kids break stuff.

This seems particularly true during the month of December. As sure as night follows day, at least one item unwrapped on Christmas morning will be reduced to smithereens by New Year’s Eve.

At the dawn of the twentieth century in the east Alabama hamlet of Roanoke, a woman named Ella Smith determined to defy the very forces of nature itself and produce an indestructible child’s toy. In the process, she launched a successful business and established herself as one of Alabama’s most notable female inventors.

Ella Louise Gauntt (sometimes spelled Gantt) was born into an artistic family in Troup County, Georgia, in 1868. She studied art at LaGrange College and, in 1886, took a teaching position at Roanoke Normal College. Four years later she married local carpenter Smiley Smith. Since teachers at the college were not allowed to be married, their nuptials brought an end to her tenure. Thereafter, she taught private art lessons in her well-appointed home.

Legends grow quickly, and deep, in Alabama soil. As such, there are several versions of Ella Smith’s origins as a doll manufacturer. One involves a young Roanoke girl named Verna Pittman, who in December 1897 arrived inconsolable at Smith’s door with a broken porcelain doll in tow. Another account names Mattie Almon as Smith’s first young patron. Armed with her artistic training, Smith labored over several years to perfect a design for a new rag doll that could withstand the rigors of play. Even the most mean-spirited youngster would find efforts to destroy an Ella Smith doll fruitless, one observer wrote. He noted cheekily that the dolls might be made of solid iron: “In a pinch, it could be a concealed weapon.”

Although her precise mixture was kept secret, the heads, hands and feet of Smith’s dolls were made of a durable plaster of Paris concoction. While the molds were still wet, she would stretch a fine mesh of cotton fibers around them, working the two materials together with her hands. The result was a smooth, paintable surface resembling popular bisque or china dolls but far less fragile.

The dolls were assembled with locally sourced materials. Neighborhood boys gathered sticks for the spines. The unrefined cotton used in the soft goods came from a Roanoke gin. Smith purchased her paints at the nearby mercantile store.

The dolls came in many sizes and with several clothing options and ranged in price from $1.15 through $12. The features of the dolls were carefully, individually painted by hand and represented, in Smith’s words, “every race of people.”

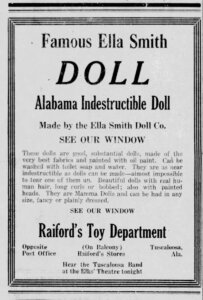

Smith took her dolls far from Randolph County, renting booths at craft shows and expositions throughout the country. She won a blue ribbon at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. During the early years of her budding enterprise, Smith did much of the work herself. But as the orders grew, her ever-helpful husband built a simple, two-story wooden factory next to their home. There, she employed about a dozen local women. In 1908, they produced a reported 8,000 handmade dolls. A brochure from the era depicted two workers seated in a corner of the factory, bathed in light as they applied the final paint touches on two 27-inch dolls. Nearby storage racks overflowed with dolls awaiting the holiday rush. “These dolls are just what the people want,” Smith wrote, “and every child is so glad to get one.” Stores throughout the South touted their inventory, particularly during the holidays.

In 1921, the dollmaker took on additional business partners. W. E. McIntosh was a wholesale grocer and part owner of a recently shuttered textile manufacturing company. B. O. Driver was a youthful second-generation Roanoke druggist and president of the chamber of commerce. The two men persuaded Smith to expand. She purchased new equipment and relocated her operation to McIntosh’s empty plant. The new partners then embarked on a northeastern sales tour. The Roanoke newspaper reported their success in securing thousands of dollars in new orders.

But it was not to be. On March 12, 1922, on the outskirts of Atlanta, the train carrying McIntosh and Driver derailed atop an embankment and plunged some 50 feet. The two Roanoke men were counted among the dead. Soon after this shock came the sober realization that the supposed orders for new dolls had never actually been placed. Months of work attempting to carry on after the accident only served to deplete Smith’s meager savings and her once seemingly inexhaustible energy. Dejected, she relocated to her original, rough-hewn facility and downsized. Two months later, she purchased W. E. McIntosh’s interest in the Ella Smith Doll Co. from his widow, an apparent settlement in lieu of a lawsuit.

Orders slowed and the inventory pile grew. Smith began offering her prized dolls at deep discounts and accepted food and home goods as payment. She died in April 1932 at the age of 63. Widower Smiley Smith moved from the couple’s home into the adjacent doll factory, where he lived until his death in 1940. During World War II, new owners renovated the old factory into rental apartments, placing several doll heads between the white latticework at the front entrance in an architectural homage to Smith.

But by 1960, most signs of the old factory were gone. Surviving Alabama Indestructible Dolls became prized possessions, frequently featured in antique shows or viewed behind museum glass. One of the African American dolls appeared on a U.S. postage stamp in 1996.

A century has now passed since the heyday of Roanoke’s doll-making empire. But residents still remember well how the Ella Smith Doll Co. helped to shape the history of their town. Local pride, after all, is a kind of indestructible thing, indeed.

Historian Scotty E. Kirkland is a freelance contributor to Business Alabama. He lives in Wetumpka.

This article appears in the December 2022 issue of Business Alabama.