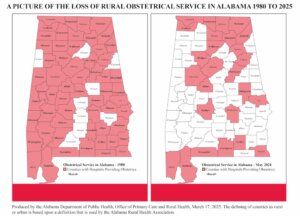

In 1980, 45 of Alabama’s 55 rural counties were home to hospitals that offered labor and delivery services. In 2025, only 15 of those counties have hospitals providing obstetrical services, according to data from the Alabama Department of Public Health.

The loss of obstetric services in rural counties means expectant mothers must travel farther to access maternal care, including labor and delivery services as well as vital prenatal and postnatal care. In a state with some of the country’s highest rates of infant mortality and maternal mortality, the loss of local maternal health is especially troubling.

But the disappearance of maternal health care is only one indication of the challenges of providing health care in rural Alabama. More than 50 hospitals in the state are considered rural, and many are struggling to provide the services needed by their communities — or even to keep their doors open.

Fortunately, the state government and the federal government have each introduced a new funding initiative that offers potential help for rural hospitals. And with the state plan, Alabama corporations can access tax credits to help rural hospitals better serve their communities.

The Alabama Rural Hospital Investment Program (RHIP) was established by the Rural Hospital Investment Act of 2025, and the federal Rural Health Transformation Program was created by the One Big Beautiful Bill passed in July 2025.

“When we were working on the state bill, we didn’t know there would be a federal bill that would create another funding opportunity for rural hospitals,” says Joseph Marchant, president and CEO at Bibb County Medical Center in Centreville, who spent three years working with State Senator April Weaver and Representative Terri Collins to develop the RHIP. “But we’re very pleased by the support and the leaders who are coming together and recognizing that we can’t stand by and watch more hospitals close.”

Challenges Faced by Rural Hospitals

The health care industry continues to face a widespread labor shortage and intense cost pressures. “All costs are up, including labor, drugs and supplies,” Marchant says. “Despite state investments in workforce, the labor shortage remains a big issue. There is a shortage of nurses and doctors and other skilled labor, but we also have a shortage of workers for housekeeping, foodservice and other roles throughout the hospital.”

While these issues exist throughout the health care industry, they deliver a harder blow to smaller hospitals in rural areas. “Rural hospitals struggle more than others because they have lower utilization,” Marchant says. “We don’t have the volume that bigger hospitals have.”

At the same time, hospitals’ bottom lines are determined by the reimbursements they receive from insurance companies and federal programs like Medicare — and Alabama has the lowest level of Medicare reimbursements in the country, Marchant says.

“Other types of businesses can raise their rates to adjust to inflation and other cost pressures,” says James Clements, CEO of Cullman Regional Medical Center, the largest independent rural hospital in the state. “But hospital rates are determined by the federal government and the managed care industry, so we don’t have that option.”

Some health care services are reimbursed at higher rates than others, relative to the cost of providing the service. So, funding generated by those services, such as surgery, can help support others that are more costly for hospitals to provide.

Rural areas also are disproportionately affected by the adoption of Medicare Advantage plans run by out-of-state insurance companies, which often don’t provide the coverage expected by policyholders, Marchant says. When those policyholders are older adults living on fixed incomes, the local hospital is often left to foot the bill for their care.

“There’s a higher penetration of Medicare Advantage plans in rural counties,” Marchant says. “In our community, 60% of Medicare customers are now in Medicare Advantage plans, up from about 40% a decade ago. Many policyholders don’t realize that their Medicare Advantage plan replaces Medicare and allows the insurance company to administer their Medicare benefit and decide what to cover.” And since many of these plans are run by large out-of-state companies, local hospitals don’t have the relationships to work through the issues with them.

Help for Rural Hospitals

Despite the challenges, rural hospitals in Alabama have new reasons for optimism. The Alabama Rural Hospital Investment Program (RHIP) is a state program that provides dollar-for-dollar tax credits to individuals and businesses that donate to eligible rural hospitals. It was modeled after the Georgia HEART Program, which has generated more than $400 million for rural hospitals in Georgia over the past eight years.

To participate in the program, rural hospitals submit applications to the state detailing the projects they hope to fund. Beginning on Jan. 5, 2026, individuals and corporations can make donations through an Alabama Department of Revenue online portal to the rural hospital of their choice. (Contributions that are not designated for a specific hospital will be routed to a rural hospital with a high financial need.) In 2026, each eligible hospital may receive donations up to $750,000. The donation limit per participating hospitals will increase to $1 million in 2027 and $1.25 million in following years.

“One of the things we’re most proud of with this program is the broad utilization that we were afforded,” Marchant says. “The program gives rural hospitals the flexibility to use the funds to invest in the workforce, aging infrastructure, new services or whatever they need in their local community.”

Bibb County plans to use any awarded monies toward adding a dialysis center. “We want to create a service that doesn’t exist in our county right now,” Marchant says. “So many people have to travel so far to get the services they need, and we want to remove that burden for our community members who need dialysis.”

Cullman Regional plans to use potential funding from the initiative to ensure the long-term availability of maternal and child health services at its hospital. “It’s the best opportunity we have to offset losses from our obstetrics and neonatal intensive care unit,” Clements says. “The new funding programs will help us increase the probability of sustainability for these programs.”

The Rural Health Transformation Program, created by the OBBA in July 2025, designated $50 billion to be allocated to approved states over five years, with $10 billion available each year from 2026 and through 2030. The goal of the program is to empower states to strengthen rural communities by improving health care access, quality and outcomes by transforming the health care delivery ecosystem. Details about how to apply for the funding have not yet been released, but Clements forecasts that the program could bring $500 million in federal funding to the state over the next five years.

And that funding could be just what the doctor ordered for these rural hospitals.

Nancy Mann Jackson and Joe De Sciose are freelance contributors to Business Alabama. She is based in Madison and he in Birmingham.

This article appears in the January 2026 issue of Business Alabama.