Miyoushi Hopkins is a rising senior at Holy Family Cristo Rey Catholic High School, and had it not been for the pandemic, she would be entering her fourth year of working while going to school.

As it is, she spent the last year getting certified in Excel and other software, but other than that, she’s spent every grade since 9th on the job and in the classroom.

That may not seem that unusual — many students work while in school — but at Holy Family, every student is required to work one day a week. And we’re not talking about shadowing or busy work. It’s real work, like Hopkins’ stint her sophomore year at Vulcan Materials.

“I worked in the rail logistics department, being sure rocks were transferred to trains properly,” she says. “I checked the spreadsheets to see where the railcars were, seeing if they got to their destination. I was the middleman between the rail company and Vulcan.”

At Holy Family Cristo Rey, there’s a lot of this going on. Every student at the school — about 200 when all four grades are combined — is required, along with their schoolwork, to share a full-time job with their team of four (one from each grade).

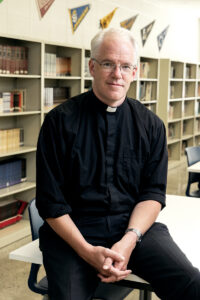

Helping to build a qualified workforce is just one goal of the 37 Cristo Rey schools around the country, which Father Jon Chalmers, president of Birmingham’s Cristo Rey school, learned about before he joined the priesthood.

“I was in graduate school in education when this model began to flourish in the late ’90s,” he says. “At the time, I was really interested in rural schools, but we knew that there was this new model that was developing for a high school on the Southside of Chicago that was really interesting. Small rural schools are what we were interested in, and this looked like kind of the urban counterpart to it.”

Chalmers earned his master’s in education, eventually married, had children and yes, became a priest, and he was working in Catholic health care in South Carolina before heading to Holy Family Cristo Rey in November 2015.

The ‘Secret Sauce’

Each Cristo Rey school must adhere to 10 “mission effectiveness standards,” but there are two standards that tower among the rest.

“The first hallmark of a Cristo Rey school is it serves an exclusively low-income population,” Chalmers says. “It’s a sliding scale depending on family size, but you wouldn’t have a family of four making more than $32,000 a year and have a student here.”

“The other hallmark is the integration of the corporate work-study program with the academic program,” he adds. “That’s kind of the secret sauce.”

Here’s how it works: Companies partner with Holy Family Cristo Rey, making jobs available to be shared among the students and paying them what is effectively part of their tuition to attend a private Catholic school. That’s about 40% of the cost. Another 40% comes from philanthropy, 15% from organizations that award scholarships in Alabama and the final 5% from the students’ families. “Everybody has to pay something, but they’re certainly not paying the cost of what tuition would be elsewhere,” Chalmers says.

But the school’s value goes far beyond the initial vision, the president says.

“This got started as a very practical and pragmatic question of how do you fund a good independent school for underserved and low-income students, and it turned into something where the students and their families win, our community wins. The school continues to function and operate, but the corporate partner has the value of the students’ work, as well as bridging some of the divides and challenges of equity and inclusion in the community.”

Holy Family Cristo Rey lists more than 50 corporate partners in its public relations material, and they include some of Birmingham’s biggest employers — Regions Bank, the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Brasfield & Gorrie, Protective Life, Alabama Power, and the list goes on.

A full team of students costs a partner $26,000, though some companies employ just one or two team members for one or two days a week. The school transports its students to their jobs via mini-bus, and to make up for lost class time, they start their regular school days a little earlier and end a little later than their counterparts.

“At any given time, we’ll have about 75% of our student body on campus and the other 25% will be out,” Chalmers says. “We function in a lot of ways like a combination of a college prep program and a temp agency.”

Success at the College Level

And it works, he says, pointing out that Cristo Rey graduates are twice as likely to graduate from college as their peers.

“Our ultimate goal is to break cycles of intergenerational poverty in urban Birmingham, but our change strategy on that is college graduation,” Chalmers says. “In addition to the income stream, there’s a raft of other benefits that are associated with graduating from college, different from almost any other type of post-secondary experiences. It builds social capital, and you tend to be happier, healthier. In a more granular way here we know that as Birmingham is continuing its transition off of a post-industrial steel economy into really a new industrial revolution wrapped around health care and digital tech and the integration of all that, we really want students who can see where the opportunity is and be qualified to engage with it.”

Before the pandemic sent students and staff home for 14 months beginning last March, Holy Family Cristo Rey — which gets support from area Catholic parishes but isn’t affiliated with one in particular — was getting settled into a new home, having renovated and moved into a former middle school in the Titusville area. Before that, the school was in a much smaller space in Ensley.

Thanks to its mission, which includes digital fluency so its students can succeed on the job, Holy Family Cristo Rey was able to pivot during the pandemic.

“That kind of saved us,” Chalmers says. “Every kid already had a Chromebook, so we were well-positioned for that, flipping into the virtual mode 14 months ago.”

Instead of going into their jobs, students, like Hopkins, spent their time learning advanced digital skills. They’ll be back on the job come fall, though.

“I can’t wait to get back,” says Hopkins, who plans to go to New York for college. “I like the school itself — the teachers, the faculty, the students — but it’s definitely the work-study aspect of it that stands out for me.”

Holy Family Cristo Rey by the numbers

24% Catholic students

76% African American students

14% Hispanic students

$32,375 Average family income, class of 2024

24 ZIP codes represented

30% GPA of 3.5 or higher