The automatic telegraph. The motion-picture machine. The alkaline battery. The light bulb. From his research laboratory, inventor and businessman Thomas Edison made the modern world possible. For more than a decade in the early 20th century, an ambitious young electrical engineer from Alabama was among his most trusted associates.

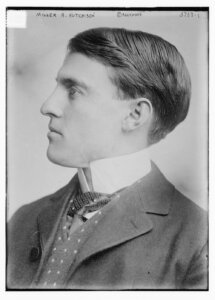

Miller Reese Hutchison was born in August 1876 in Montrose, where his parents had a summer home. His father was a broker in Mobile. His mother’s family were landowners near Tuskegee. In machine shops and foundries around Mobile, an inquisitive young Miller Hutchison spent his childhood years. As an adolescent, he enrolled at Marion Military Institute. He later took classes closer to his Mobile home, at Spring Hill College and the University Military School. He studied electrical engineering at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (API) as part of the Class of 1897. There, before his 20th birthday, Hutchison received his first patent for a device to protect telegraph wires from power surges and lightning.

The Alabama inventor’s two greatest contributions came in the years before his association with Edison. The first was an electrical hearing aid marketed as the Acousticon. Hutchison spent time at Mobile’s Medical College studying the anatomy of the ear to create the device. Patented in 1902 and widely distributed, the device garnered acclaim on two continents and made Hutchison a rich man. Queen Alexandra of England bestowed upon him a medal of merit in recognition of his work to assist the deaf. Only after her death in 1925 was it revealed that the queen had availed herself of Hutchison’s invention. It was a secret well kept.

Hutchison transferred the Acousticon’s commercial rights to an associate in 1905. The following year, he filed a patent application for a new invention: the Klaxon horn. In the Greek language, klaxo means “shriek.” The horn, with its distinctive, ahh-oooh-gahh sound, was appropriately named and designed to rise above the noise of the street. American humorist Mark Twain once suggested that Hutchison created the Klaxon horn to drum up business for his hearing aids. In 1910, Hutchison’s Klaxon royalties exceeded $41,000 (nearly $1.5 million today). By 1912, Klaxons were standard on all new General Motors vehicles.

He was 34 when he walked into Edison’s lab in West Orange, New Jersey, with a new proposal in the summer of 1910. By that time, Hutchison was a respected engineer and inventor and a wealthy, well-connected man. He proposed a partnership to outfit submarines and other naval vessels with versions of Edison’s electric batteries. The possibility of lucrative military contracts was too good to ignore. The business-minded Edison agreed and retained Hutchison.

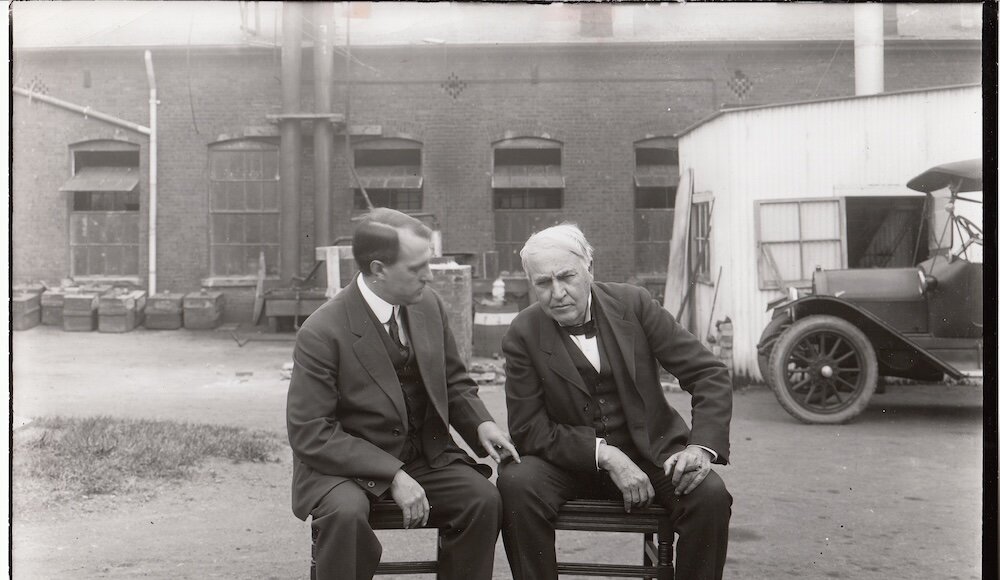

Hutchison proved himself a keen interlocutor, particularly in the halls of government. The taciturn Edison came to enjoy the company of the man from Alabama. “They presented an amusing contrast when seen together,” wrote Edison biographer Edmund Morris. “The younger man, saturnine, elegant in dress and manners, smoking choice Havana cigars; the older white-haired and slovenly in suits that had often been slept in, chomping on a wad of the cheapest tobacco.”

For the next several years, they worked alongside each other and traveled together in Hutchison’s Packard. “He is opening up to me more and more all the time,” Hutchison wrote in his diary. By the time of their association, Edison was quite deaf and refused the use of any hearing aid. In meetings, “Hutch,” as he was called, would sit at Edison’s right side, tapping out pertinent details in Morse code onto the great inventor’s knee. “I am ensconced here,” Hutchison wrote in his diary in 1912, the same year Edison named him as his chief engineer, “right next to the greatest living inventor & apt to step into his shoes when he passes away. Brillant future ahead of me.”

Edison’s family had something to say about this plan of succession. The inventor’s wife, Mina, feared “Hutch” might supplant Edison’s son, Charles, as heir apparent. But this was not to be. A deadly 1916 accident aboard a submarine outfitted with an Edison-made battery damaged the relationship between the two inventors. Although blamed on improper ventilation rather than manufacturer error, the incident marred the reputations of Edison and Hutchison. The U.S. Navy’s inquiry into the explosion lasted for some time. “We were in no way to blame,” Hutchison wrote in his diary, “but the odium has gone all over.”

Hutchison’s association with Edison Labs came to an end in 1918, after eight years, including six as chief engineer. Charles Edison, now chairman of the board, canceled Hutchison’s commission. The elder Edison offered no protest. The split was amicable; the severance was substantial. But “Hutch” departed West Orange with more than money, however. “I spent the happiest days of my life with Edison,” he later recalled.

He settled in New York City, hanging his own corporate shingle on the 51st floor of the Woolworth Building. At the time, it was the tallest building in the world, a fitting location for a man of such ambition who had achieved so much by the age of 42. There he continued in his own inventions for many years, including enhanced safety devices for aircraft and a compound to reduce the amount of carbon monoxide in fuel exhaust, to name only two.

Although his work had taken him far from the Yellowhammer State, Hutchison maintained close Alabama ties. Hutchison donated frequently to API fundraising campaigns and spearheaded a gathering of alumni in Manhattan. He accepted many a speaking invitation postmarked from his native land. At commencement exercises at Mobile’s University Military School, Hutchison urged graduates “Stay South, young man, stay South…. Here there are great possibilities.” He lent his expertise to ridding the land of the boll weevil, the tiny, foreign scourge that had so devastated Alabama farms. At the State Capitol, he lobbied legislators to raise the educational standards in Alabama’s public schools.

Miller Reese Hutchison died in February 1944 at the age of 67. Observers praised him as one of the most creative and consequential minds Alabama ever produced.

Historian Scotty E. Kirkland is a freelance contributor to Business Alabama. He lives in Wetumpka.

This article appears in the January 2026 issue of Business Alabama.