Walking through the grounds of Kymulga Grist Mill Park near Childersburg is a portal into Alabama’s blue-collar business history. Amidst the tall white oaks and the gentle hum of water falling over what remains of a 19th century dam, it’s easy to ignore the electrical lines, RVs and other trappings of modern life now in view. Since the days of the Civil War, cornmeal, flour and feed have been prepared in this towering wooden structure.

The idea for the mill came from George H. Forney, the seventh child born to Jacob and Sabina Forney. The family relocated from North Carolina to Jacksonville, Alabama, after George’s birth. The elder Forney and his son, Joseph, were merchants. When Jacob Forney died in 1856, young George took his place in the company.

When the Civil War began, all five of Jacksonville’s Forney men joined the Confederate cause. George Forney signed on with a Calhoun County militia group. By 1862, he had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the 1st Confederate Infantry Battalion.

How George Forney came to learn of the burgeoning settlement in Talladega County named Kymulga is not clear. But in the midst of his service to the Confederacy, he purchased land there and contracted with a South Carolina millwright named G. E. Morris to build a grist mill. Forney rightly discerned the appropriateness of the site for such a venture. The land was along the Old Georgia Road, where a newly constructed covered bridge crossed Talladega Creek. A railroad track bounded the other side of the property. Here were all the elements of a true crossroads community, with room for homes and businesses. Morris and a crew of enslaved laborers began working on the mill’s foundation, dug a canal to divert portions of the creek to power the turbines and set in place a sturdy, seven-foot reservoir dam.

But in the spring of 1864, Forney’s postwar plans for Kymulga died with him on a Virginia battlefield. Fellow soldiers brought his uniform back to his family in Jacksonville. When his mother died in 1881, those items were buried with her. A stained-glass window at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Jacksonville, where the Forneys worshipped, is dedicated to his memory.

The Forneys instructed G. E. Morris to finish Kymulga Mill. The builder remained there for several years thereafter. Before the end of the war, many of the grist mills in the region fell victim to raiding Union soldiers. But Kymulga escaped the torch, in part because it was so difficult to find.

Construction was protracted, owing to the upheaval and uncertainty of the era. Thus, the project spanned the years from bondage to freedom for Morris’ enslaved workers. Skilled in construction and design, many of these men elected to stay on with Morris as paid employees. One of these men, whose name is lost to history, was entrusted with the essential task of hauling the five hulking French buhrstones for grinding the grain from the docks of Mobile to the site with a team of oxen.

Morris and the craftsmen did their work well. Kymulga Mill is renowned for its construction and ornamentation, including its attractive gables and a circular window just below the roofline, an architectural jewel atop a building made for work.

William Baker, a Talladega businessman and sometimes politician, purchased the mill in the 1870s. He expanded its production capacity to 600 bushels of grain per day.

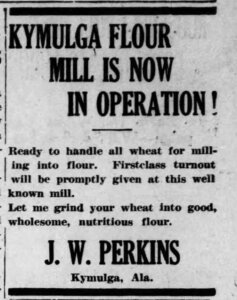

Baker understood publicity. In October 1877, he gave the editors of a local newspaper a 100-pound sample of his best flour. They offered their thanks in the form of an editorial endorsement.

It was Baker who brought George Forney’s commercial aspirations to reality. A production schedule for 1879 shows that the Kymulga Mill produced 40,000 bushels of wheat, 46,800 bushels of other grains, 726,000 pounds of livestock feed and an astounding 2 million pounds of corn meal. The annual combined value of these products was nearly $73,000 ($2.5 million today). This was unhurried work. Farmers and merchants would sometimes wait several days for their turn at Kymulga, camping out at the site or taking a room nearby. By the mid-1880s, Kymulga was described as “one of the liveliest places in the county,” with the grist mill as well as a sawmill and cotton gin.

A series of owners followed after William Baker’s death in 1895. As the years passed, the large stones of the mill continued to grind. In the modern era, the mill’s sustained operation, and the bucolic scene it set with the nearby bridge, was trumpeted in the pages of Alabama newspapers, a reminder of a different era, a simpler time. “CENTURY-OLD MILL STILL GRINDS AWAY IN THE SHADOW OF A COVERED BRIDGE,” read the headline of one article from 1970. That year, owner John Carter produced 4,500 bushels at Kymulga Mill.

The mill and bridge were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. At the time, the mill was operated by L. E. Donahoo, a local who was later honored for his efforts to preserve the structure. To him, Kymulga Mill was like an old friend. “I been knowing it 57 years of my life,” he told a reporter.

In 2011, the city of Childersburg acquired the property and established a park. They assigned its upkeep to the local historic preservation commission. Storms the following year almost destroyed the mill when floodwaters washed out part of its foundation. Determined not to let Mother Nature succeed where even the Union Army had failed, the commission shored up the building, at a cost of more than $250,000.

Thanks to caretakers across generations, the mill and bridge at Kymulga are still standing, and the mill still operates on special occasions. For a small admission price, you can walk the grounds. If you’re lucky enough to be there on the right day, you can do something founder George Forney never lived to do: you can walk inside his grist mill and see the intricate detail that went into its construction and more than a century of history.

Historian Scotty E. Kirkland is a freelance contributor to Business Alabama. He lives in Wetumpka.

This article appears in the April 2025 issue of Business Alabama.